LBJ IS SWORN IN AS

PRESIDENT

|

|

Lady

Byrd, LBJ and Jackie Kennedy aboard Air Force One

|

|

Type of Activity

|

Political Rally and Motorcade

|

Location

|

|

Location

|

Dallas, Texas

|

Date of Activity

|

22 N0v. 1963

|

Coordinates

|

|

|

| President and Mrs. Kennedy deplane in Dallas |

|

| Vice President and Mrs. Johnson at Love Field |

|

| The Presidential Motorcade Departs Love Field |

|

LBJ receives the oath of office aboard AF-1 |

LBJ would serve out JFK’s term as President; he ran for reelection in 1964 and won. It was later in 1965 that I was interviewed and accepted an assignment with the White House Communications Agency and spent nine years providing communications for the White House!

The WHCA AFTER ACTION REPORTS OF NOVEMBER 22, 1963THE WHITE HOUSEWASHINGTONApril 1, 1997Ronald G. HaronSenior AttorneyAssassinations Records Review Board600 E. Street 2nd FloorWashington D.C. 20530Dear Mr. Haron,White House Communications Agency (WHCA) has searched their files for assassination-related records and was able to locate several statements from WHCA personnel who were on duty at various locations at the time of the assassination of President Kennedy. These statements were found in a folder titled “PRES KENNEDY ASSASSINAITON”. Copies of the statements are attached. There is no other assassination related material in the folder, except the list of telephone calls recorded by the White House switchboard on 22 November 1963, previously forwarded to your office.The WHCA has completed its assassination-related records search.SincerelySIGNEDGregory G. RathsLt. Col. USMCAssistant Chief of StaffWhite House OfficeWhite House Communications Agency (WHCA) Communications Center SwitchboardRadio Operators after Action Reports[BK Notes: Many thanks to Doug Horne for providing these records]

The Dallas White House switchboard had been established in the Sheraton-Dallas Hotel WHCA Trip Officer for Presidential Visit to Dallas, TexasCWO Arthur W. Bales, Jr.The following is approximately the sequence of events, as recalled by the undersigned, in Dallas, Texas, 22 November 1963

THE WHITE HOUSE COMMUNICATIONS BRANCH

SUBJECT: Sequence of Events – 22 November 1963

TO: Commanding Officer, WHCA

1. Prior Communications Arrangements: The Dallas White House had been established in the Sheraton-Dallas Hotel, and Communications facilities included a one-position switchboard with 3 dial trunks, 2 LD’s 3 tie lines to the Fort Worth White House Board, 1 tie line to the Sheraton-Dallas Hotel Bd., 3 extensions to Love Field, 4 extensions to the Dallas Trade Mart (site of the President’s scheduled speech), secure teletype equipment, and radio and phone patch facilities to cover the motorcade.

2. Planned schedule of Events: The undersigned was to cover the President’s arrival at Love Field and, with the Special WHCA Courier, travel in the motorcade and cover all stops to include the President’s departure from Dallas. SSGT Robert D. Brazell, with six men, were manning the Dallas White House; and seven men, making the Texas circuit aboard the Press Plane, were to remain at Love Field, as they would not be needed in Dallas. A recoding technician, Specialist John Muhlers, was set up and stationed at the Dallas Trade Mart to record the President’s speech and to furnish audio feeds to the various news media.

3. The arrival and Motorcade: Air Force One landed and the President spent some time shaking hands and greeting the large crowd at Love Field. The motorcade then departed for the trip through downtown Dallas and to the Trade Mart. In the WHCA Communications Car were: A telco driver; the undersigned WHCA Advance Officer; the WHCA Courier, Mr. Gearheart; and the Telco special representative (or “Shadow”), Mr. Herb Smith. We were approximately six cars and two (Press and Staff) buses behind the President. The motorcade had just passed the last buildings on the route before entering the freeway to the Trade Mart. The WHCA Communications Car was around two corners from and not in sight of the President’s car. Three explosions were heard, and I thought that they were backfires from vehicles up ahead. Herb Smith remarked that firecrackers were inappropriate for the occasion. Then the USSS Agent riding with the President announced on the FM “Charlie” radio, Lawson, he’s hit”. The motorcade came to an abrupt halt with one bus and the WHCA car still around two corners from the President. Realizing that emergency communications facilities may be required on the spot, I instructed the driver to get Mr. Gearhart immediately to the vicinity of the President and to keep him there regardless of my own location. I, with the Telco representative, Mr. Smith, then started running toward the scene of the shooting. As we rounded the first corner the motorcade suddenly raced away. I commandeered a police car and instructed the driver to take us immediately to the Parkland Hospital. We arrived short minutes after the President.4. The Parkland Hospital: The very limited telephone facilities at the hospital were tired up by the members of the Press Pool. I immediately seized all but one line (leaving Merriman Smith on the one most remote from the Emergency Rooms) and established direct circuits to the Signal Board in Washington; the Dallas White House Switchboard; and to the Signal board via the Dallas and Fort Worth White House Boards. I assigned police officers to guard these phones and instructed the individual Signal Operators in Washington who were on these circuits to handle no other calls, but to guard these lines exclusively. I then ordered six lines in to the hospital from the Dallas White House Board and informed appropriate White House Aides of my actions. I then checked back with the Dallas White House and learned that SSGT Brazell had, on is own initiative, ordered in an additional switchboard position, 3 additional dial trunks, 4 trunks to Washington, and had alerted Telco to the possibility of further TTY facilities being required. I instructed SSGT Brazell to direct four of the seven men (Press Plane Riders) at Love Field to report to me at the hospital, and the other three reports to him at the hotel. The six lines to the hospital, the four trunks to Washington, and the additional TTY facilities were cancelled before completion. As the WHCA personnel arrived from Love Field, they replaced the police officers who had been guarding the seized telephone lines. At the appropriate time I instructed Mr. Gearhart to remain with the President Johnson, and they left shortly for Love Field. I remained at the hospital and later went to the field with (the body of) President Kennedy and Mrs. Kennedy, instructing the WHCA personnel to remain at the hospital until released by the White House Staff personnel who were remaining there a while longer. Meanwhile, I had advised Captain Stoughton, WHCA Photographer, and SP5 Muler (Recording – stationed at the Trade Mart) of President Johnson’s return to Air Force One: enabling Captain Stoughton to be the only photographer aboard when the President took his oath of office. Muler recorded the proceedings, and the tape was returned to Washington via Colonel McNally aboard the Press Plane.ARTHUR W. BALES, JR.

CWO USA

Trip Officer

Chief Switchboard Operator White House Switchboard in Dallas, Texas

SSG Robert Brazell

The following is approximately the sequence of events, as recalled by the undersigned, in Dallas, Texas, 22 November 1963PHYSICAL SITUATION1. 1 Position 555 PBX trunking to Washington through Ft. Worth with no direct connection to Washington.

2. 3 City Dials

3. 3 LD Toll Terminals

4. Radio on top of PBX

CHRONOLOGICAL SEQUENCE OF EVENTS1. Complete relaxation waiting for parade to arrive at luncheon site.2. (1230) A Sudden blearing of radio “Lead us straight to the hospital he’s been shot – repetition “He’s been shot.”3. Realization of inadequate facilities to handle any emergency of this type.4. Placed order for additional 555 positions, additional dial trunks and more extensions in the Room even before the party arrived at the hospital.5. Party reached hospital and all dial trunks lit up immediately.6. Direct connection set up immediately between Agent directly outside of emergency room and Mr. Behn in his office in Washington which became the Washington Command Post and he cleared the house. Ordered to monitor the circuit which was done to the best of our ability, on top of moving regular traffic7. Calls from members of the President’s family bridged into the Behn-Emergency room focus. (E.g. Attorney General asked whether a priest had been called.)8. Constant advisement on the location of the Vice President.9. Made arrangements with police to have WHCA Press Plane party rushed to hotel for use as needed.10. Dispatch of part of this contingent to assist at the hospital on CWO Bales’ orders.11. Mr. Kilduff ordered the return of the delegation enroute to Japan immediately upon perceiving the seriousness of the situation. Placing of this in the hands of the WHCA Duty Officer in Washington.12. Answering calls with extension on top of PBX; then routing them to proper spot. Utilized radio man Lukens on “hold and wait” calls.13. President Johnson returns to aircraft.14. Second peak of calls for day doing such things as finding Judge Sarah T. Hughes to swear in the President and find someone in the Department of Justice to dictate the oath of office. Vice President Johnson personally spoke to the clerk In Judge Hughes’ Office.15. By this time the telephone company had performed a near miracle and installed the second 555 position with three additional dial trunks on it.16. An effort was being made to bring up four full periods back to Washington but desisted when It became obvious that the need for them was almost over.17. as a general comment: enough traffic passed through that one position 555 as should normally have gone through a 3-position PBX at full throttle.SSgt BrazellPS: The Switchboard operator recalls placing a call from Attorney General to Air Force One prior to the swearing in ceremonies; he does not know to whom he spoke but feels it was to the Vice President.

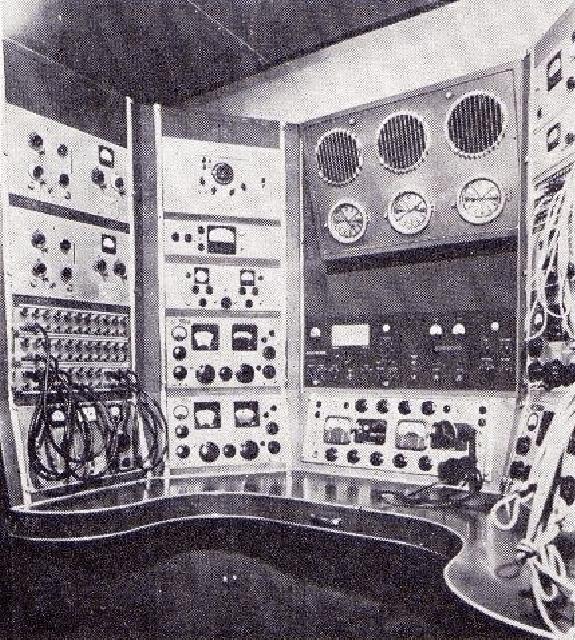

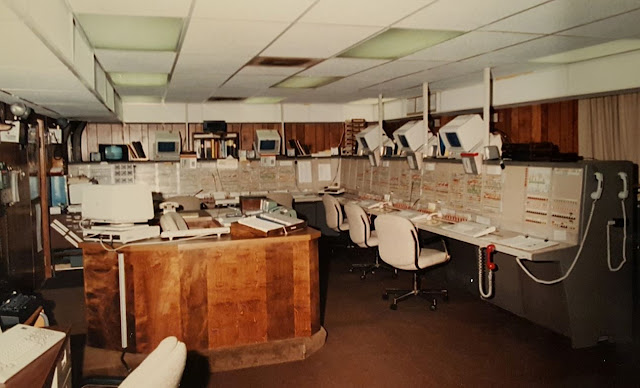

WHCA Signal Board and Communications Center handled traffic from Dallas and other sources.

|

| Air Force One 26000 Radio Console |

| |||

Type Of Activity | Presidential Speeches | ||

Location | |||

Location | Washington DC and various Locations | ||

Date of Activity | 1963 to Present | ||

Coordinates | |||

The Presidency of any country is aptly described as the most demanding job in the world. Zero in on the United States presidency, and you can easily multiply the difficulty a thousand times. Besides the many issues, state visits, rubbing elbows with influential people, and whatnot, state presidents also deliver speeches every now and then. They may do so in front of the media, in a live audience on a worldwide broadcast, or a combination of both.

It’s a part of a President’s job to present dozens of speeches, but to be honest, it’s the least of his worries. Why? It’s because he has access to the best equipment, such as a teleprompter, specifically a presidential teleprompter operated by the professionals of the White House Communications Agency.

WHCA has long been for responsible all audio and video at Trip sites including the presidential podium and teleprompter.

Brief History of Teleprompter Use by U.S. Presidents

Four years after the invention of the teleprompter in 1948, General Dwight Eisenhower was the first to use it in a campaign speech in September 1952, The 1952 Republican National Convention was the first political convention broadcast live by television. In addition to being the first live telecast, the GOP convention was the debut event for the new device still used by politicians today, the “TelePrompTer”. As the keynote speaker for the convention, former president Hebert Hoover used the TelePrompTer, however, without much success.

The teleprompter quickly became a fixture of political campaigning and speechmaking, being utilized for the first time in 1954 by President Dwight Eisenhower for a State of the Union address.

President Johnson was the first President to require a teleprompter at all of his speeches, at this point in time WHCA was building and setting up LBJ’s bulletproof Podium at all speech sites, recording all of his speeches, providing the PA system and an audio feed to all of the networks.

General Jack Albright, WHCA CO, recalls his early days with LBJ “As time went on, he wanted more things. He wanted to be able to read his speech while looking at the audience, and so we turned to the philosophy of the teleprompter. We signed a contract with a New York company, and they provided us with a great number of teleprompters. Now, these were heavy, very heavy things to haul around.

|

| The cabinets in front of LBJ was in 3 pieces.. extremely heavy especially when we installed the bullet proof shield. |

At this time, the presidential teleprompter was massive and very obvious to individuals in the audience. The early teleprompters used a VERY LARGE typewriter that would put the text on a half inch gummed tape that was then pasted onto a roll of teletype yellow paper. It was very hard to cut and paste to make edits, and LBJ didn’t like handwritten comments in margins.

"The print was about a half inch high, so, the President had little trouble reading it. He could read it either directly ahead of him or to either side of something like a forty-five-degree angle from that. That's the first innovation WHCA put in.” according to BG Albright.

|

| A WHCA operator typing a speech |

|

| President welcomes home the 1st Marine Div. returning from Vietnam The most important speech that President Ford gave was a rare Sunday afternoon speech to announce his pardon of President Nixon. ... No teleprompter, just note cards. It was perfect for the time. President Ford usually wore contact lenses when he used a teleprompter to avoid the use of his glasses while making speeches. |

|

| President Ford pardons Richard Nixon |

|

| 1980 Democrat Convention in Madison Square Garden |

Ronald Reagan regularly used a teleprompter during all of his speeches. President Reagan, often spoken of as "the great communicator," was noticeably at a loss for words when his teleprompter broke down during a major speech before the European Parliament in Strasbourg, France . Reagan's teleprompter cut out three times causing the president to lose his place... Nonetheless, after a short period of time he recovered and continued. The President took everything in stride.

|

| President Reagan uses the dual glass teleprompter setup |

|

| Small podium requested by President Reagan |

|

| Teleprompters are always available even if the President doesn’t use it |

Today, you rarely see a President, or any country leader speak to a live audience without a teleprompter. From the printed scrolls to LCD monitors, automatic scrolling on an Atari PC to voice recognition, the teleprompter truly changed the landscape of political speeches, often for the better.

As a result, this teleprompter is more commonly used for giving speeches, as it lets the speaker see the audience through the glass. Another advantage of this teleprompter is that multiple monitors may be positioned throughout the arena, allowing the speaker to stare at the entire crowd during their speech, making it appear even more natural.

Just because a teleprompter makes the Presidents life easier, it doesn’t mean he would be good at it without practice or some tricks he could use. In fact, not every United States president presents a speech using a prompter. Some, like George W. Bush, disliked teleprompters and preferred large index cards while President Trump prefers the presidential teleprompter for all of his speeches.

|

| President Trump uses the Teleprompter for every speech |

|

| Today’s Presidential teleprompter setup for all speeches |

The flawless delivery of a speech begins long before the President steps onto the stage. It starts with meticulous preparation and the setup of the presidential teleprompter and podium. Here's a glimpse of some of what the WHCA A/V teleprompter operator does behind the scenes before a crucial event:

1. Review: WHCA A/V operator typically starts with a thorough review of the President’s speech. The speech is loaded onto the teleprompter's software, where the operator can format it for optimal readability, adjusting font size and scroll speed according to the speaker's preference.

2. Equipment Check: Ensuring that all equipment is in perfect working order is paramount. This includes not only the presidential teleprompter and its screen but also the control devices and any backup systems in case of technical glitches.

3. Operator Briefing: The teleprompter operator, a crucial part of the team, receives instructions and must become familiar with the Presidents delivery style and pace. They must be in sync with the President to ensure seamless scrolling of the script.

4. Rehearsals: Depending on the importance of the event, the President might run through the speech using the teleprompter several times to ensure comfort and familiarity with the setup. This rehearsal helps eliminate last-minute surprises or hiccups.

5. Backup Plans: While the teleprompters are always backed up the White House Staff often has printed copies of the speech, just in case of technical difficulties.

B. Positioning and Testing the Teleprompter

The physical placement and calibration of the teleprompter is critical for a successful presentation. Here's a step-by-step breakdown of how it's done:

1. Stage Placement: The teleprompter is positioned directly in front of the podium, at eye level, to ensure that the text is easily readable without the need for the President to look down or significantly off axis. This positioning allows for the appearance of uninterrupted eye contact with the audience.

2. Glass Angling: The glass or reflective surface of the teleprompter is angled to reflect the text from a screen placed below the stage. This positioning, sometimes using a one-way mirror, ensures that the text is not visible to the audience while remaining clear to the speaker.

3. Adjusting Font Size: The teleprompter operator adjusts the font size and scroll speed to match the Presidents preference. The text should scroll at a pace that feels natural to the speaker, allowing them to maintain a smooth and coherent delivery.

4. Testing Visibility: Before the event begins, a final test ensures that the text is perfectly visible to the President without any glare or distortion. This may involve adjusting the angle or lighting around the teleprompter to optimize readability.

5. Technical Checks: The teleprompter operator performs one last technical check to ensure that the software, controls, and connections are functioning flawlessly. The President can also have a final run-through to make any last-minute adjustments or clarifications.

The behind-the-scenes world of the presidential teleprompter operator is a fascinating and essential part of modern-day public speaking. The teleprompter has evolved from its mechanical origins to become a sophisticated digital aid for all presidential speeches. It helps maintain eye contact, enhance public speaking skills, and reduce the likelihood of mistakes, playing a crucial role in delivering speeches with confidence and precision. The setup involves meticulous preparation, equipment checks, and operator briefings, resulting in a seamless and invisible presence on the stage, offering the audience a flawless presentation. The presidential teleprompter remains vital for effective communication for world leaders and political speakers.

The White House Communications Agency (WHCA) Audio Visual (AV) team provides all necessary equipment and personnel, primarily sourced from WHCA’s Anacostia facility, for presidential and vice-presidential speeches. While approved subcontractors may sometimes be utilized, WHCA AV retains full responsibility for all services. These typically include teleprompter operations, broadcast audio and public address systems, video recording, and livestreaming. Additionally, WHCA AV supplies unique White House equipment such as presidential podiums, seals, and flags. For indoor events, lighting and sound support are essential. The venue, staging, and backdrops are also prepared by White House staff, ensuring the President is ready to deliver the speech.

Air Force One SAM 96970, 26000 and 27000 (1962-2001) | |

Type Of Activity | Presidential Transport |

Location | |

Location | Worldwide |

Date of Activity | Oct 1962 to June 2001 |

Coordinates | 33°40′34″N 117°43′52″W |

President Dwight Eisenhower became the first US president to travel by jet when he flew on a new Air Force One plane in 1959. Eisenhower's Boeing 707 Stratoliner, nicknamed "Queenie," featured a section for telecommunications, room for 40 passengers, a conference area, and a stateroom, The jet, known as SAM (Special Air Missions) 96970, was customized to meet the needs of the president and White House staff.

In 1959, the Boeing 707-153 known as SAM 96970 became the new presidential aircraft, replacing the propeller-powered C-121C Super Constellation used by President Dwight Eisenhower. SAM 96970 was part of the VC-137 series of planes.

In 1962, a newer VC-137C plane replaced it as the primary presidential aircraft, but it still transported vice presidents and other VIPs. The SAM 96970 remained part of the presidential fleet until 1996.

The new primary presidential aircraft number SAM 26000, was a specially configured Boeing 707-353B with the Air Force designation C-137C.

The SAM 96970, SAM 26000 along with SAM 27000 are the most Iconic presidential aircraft to date. All the C-137C's were part of a fleet of aircraft maintained by the Military Airlift Command's 89th Military Airlift Wing, Andrews Air Force Base, Md.

When the president is aboard either aircraft, or any other Air Force aircraft, the radio call sign "Air Force One" is used for all communications and air traffic control identification purposes.

Principal differences between the C-137C and the standard Boeing 707 aircraft are the electronic and communications equipment carried by the presidential aircraft, and its interior configuration and furnishings. Passenger cabins are partitioned into several sections: a communications center, the presidential quarters, and a staff/office compartment. There is limited seating for passengers, including members of the news media.

|

| President Kennedy and the First Lady arrive at a rally in Houston |

|

| LBJ visits Vietnam in 1965 unannounced while attending the Manila Summit Conference |

|

| Air Force One at El Toro MCAS while visiting San Clemente |

His most widely heralded trips included the around-the-world trip in July 1969, to the Peoples Republic of China in February 1972, and to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in May· of that same year.

|

| President Nixon dubbed SAM 2600 the Spirt of 76 a short time before leaving for Beijing |

|

| President Ford arrives in Chicago Note: The state of the art Ramp Phone |

|

| President Ford on one of his overseas trips on SAM 27000 in 1975 |

|

| President Reagan stops by the Communications Center aboard SAM 27000 |

| |||||||||||||||||

| USAF VC-137C Communications Systems Operator using Kleinschmidt terminal (1970s or early 1980s) From the plane, the president could reach the White House Situation Room and the National Military Command Center and send secret communications. Across from the communication station, the briefcase containing codes to initiate a nuclear strike was kept locked in a safe. Known as the " nuclear football ," every president since Eisenhower has been accompanied by the briefcase at all times. The safe also held military communication center codes. In the forward galley, crew members prepared food and drinks for the president and other crew members or White House Staff. The two galleys on Air Force One included ovens, refrigerators, and open-burner stovetops. Drink dispensers also served coffee, water, and other beverages.

The aft galley served food and drinks to senior staff and the press. Like the forward galley, the aft galley was furnished with kitchen appliances and drink dispensers.

The staff seating area looked the most like regular economy cabin seats while members of the press sat further back on the plane. The staff seating area looked the most similar to regular economy cabin seats. White House staffers and cabinet members who joined the president on trips sat in the staff seating area.

Retired in 1996, SAM 96970 now on display at the Museum of Flight in Seattle. SAM 970 was a VC-137 series used by Eisenhower as well as Presidents John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, and Richard Nixon as their primary aircraft. The Presidential Aircraft SAM 26000 with the Air Force designation C-137C. was officially retired in 1998 and is on display at Wright-Patterson AFB, near Dayton OH. Served Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan, George H.W. Bush and Clinton. SAM 27000 a modified C-137C served Presidents Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan, and George H.W. Bush. SAM 27000 has been on display at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Semi Valley CA since 2005. |

Power plant/manufacturer: Four Pratt & Whitney JT3D-3B turbofan engines

The Presidential Service Badge | |||

| |||

| Type of Activity | Communications support for the White House | ||

Location | |||

| Location | Washington DC | ||

| Date of Activity | Mar 1942 to Present | ||

| Coordinates | 38°53′52″N 77°02′11″W | ||

Establishing Authority

Background

The ranch is located on the north side of United States Route 290, about fourteen miles west of Johnson City, which lies between the highway and the south bank of the Pedernales River.

It is now a National Park that protects the birthplace, home, ranch, and final resting place of Lyndon B. Johnson, 36th President of the United States. During Johnson's administration, the LBJ Ranch was known as the "Texas White House" because the President spent approximately 20% of his time in office there.

On July 12, 1952, they moved into their ranch home. To commemorate the event, LBJ took a small limb and scratched in the concrete ...walkway near the south gate, the date and "Welcome to the LBJ Ranch."

|

The President enjoys the Ranch with his family |

|

| LBJ’s Office at the Ranch |

|

| LBJ’s Office at the Ranch |

|

| LBJ holds a meeting in the ranch’s living room |

|

| LBJ holds a meeting in the ranch’s living room |

|

| The Living room at the Ranch |

THE PRESIDENT'S BEDROOM

|

| The President's Bedroom |

|

| The President's Bedroom |

|

A JetStar or similar aircraft usually landed at the ranch |

|

| James Cross LBJ’s pilot seen here with the JetStar |

|

| Interior of the JetStar |

|

| Hanger Area also WHCA Comm. Trailers and USSS Command Post |

|

The hanger area and Airstrip at the LBJ Texas Ranch Compound |

|

Secret Service Guard Shack |

|

| Aerial View of the entire Compound of the LBJ Texas Ranch WHCA and USSS CP left of the hanger |

|

| The Texas White House Compound, |

White House Voice Recording Systems | |

Type of Activity | Tape Recording Conversations |

Location | |

Location | Washington DC and Others |

Date of Activity | 1940 through 1974 and maybe more |

Coordinates | 38°53'51.2"N 77°02'20.9"W |

|

A Model 5 reel-to-reel magnetic tape recorder made by Tandberg Radiofabrikk was installed in 1962 during John F. Kennedy’s presidency. |

|

| President Johnson looks at the news feed and watches his Three Eyed Monster in the oval Office |

|

| The President’s desk in the Oval Office |

|

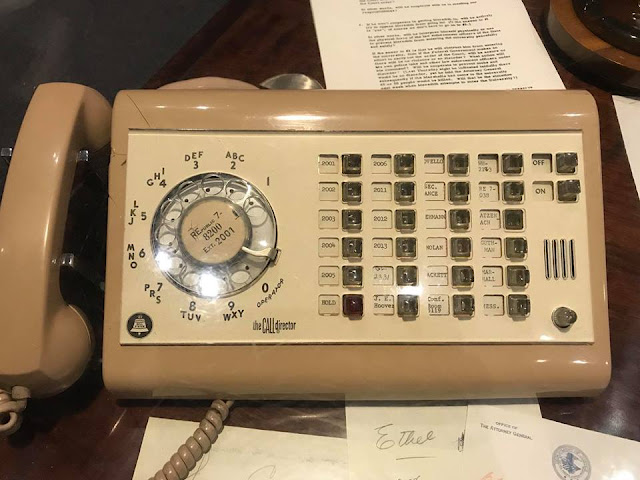

| Call Director on the President’s desk |

|

| The coffee table with Phone |

|

| LBJ in the cabinet meeting room |

|

| President Richard M. Nixon used voice-activated Sony TC-800B reel-to-reel tape recorders. |

The taping system began operating in the Oval Office and the Cabinet Room on February 16, 1971. On April 6, the president's office in the Old Executive Office Building and his telephones in both this office and the Oval Office, and the telephone in the Lincoln Sitting Room in the Residence, were added to the system. Over a year later, on May 18, 1972, the president's office and two telephones in Aspen Lodge at Camp David were also added to the system, The Camp David installation completed the system.

|

| Microphone locations in the Oval Office Enlarge |

|

| The Cabinet Meeting Room |

|

| Rose Mary Woods, President Richard Nixon's secretary transcribing recorded tapes |

LBJ Communicating with the World (1966) | |||

| |||

Type of Activity | Communications | ||

Location | |||

Location | Worldwide | ||

Date of Activity | August 1967 | ||

Coordinates | 38°53'51.2"N 77°02'20.9"W | ||

Note: Excerpts from an Article found in the Bell Telephone Magazine, Spring 1966, Titled, Communicating Presidents by Merriman Smith was used in this Post.

|

| WHCA HF Radio Console |

|

| President’s Office on Air Force One |

|

| Air Force One's HF Radio Console |

|

| Working aboard Air Force One |

|

| LBJ's Office at his Texas ranch |

|

| The White House Admin Switchboard 1967 |

"Is Mrs. Johnson around?"

"One moment, sir," comes the crisp voice of a secretary.

"Fine, dear, everything is ready."

|

| FM Radio telephone in the rear seat of the limo. |

A temporary trip switchboard installed to handle all telephone and radio traffic during the event. |

| When needed, these hand-sized, miniaturized transceivers are connectible with telephone land-lines. If the trip involves several cities, it is quite common, for example, to hear one of the President's assistants using a handi-talkie to the travelling White House switchboard, operated in conjunction with the radio base station, to check plans with a White House advance man several hundred miles away. |

|

| LBJ Oval Office |

Air Force One SAM 26000 Radio Console Type of Activity

Air Transport

Location

Location

Worldwide

Date of Activity

Oct 1962 to June 2001

Coordinates

33°40′34″N 117°43′52″W

The UHF system WHCA operated (on 415.7/407.85) is code named "Echo Foxtrot", or "Nationwide" (the later name distinguishes it from the "Washington Area" system used for communications with White House limos and staff cars). It provides full duplex clear voice coverage over most of the continental US to VIP aircraft in flight (SAM aircraft - Special Air Missions - which fly out of Andrews AFB). It links them to a console Crown Radio at the White House Switchboard ("Crown") in the Old Executive Office building basement from which phone patch connections can be made to telephones at the White House, on the commercial POTS/DDD network, various other federal telephone systems, and occasionally the DSN (Defense Switched Network - formally Autovon).

White House Signal Switchboard ("Crown")

Crown Radio had two consoles one was the Washington DC FM network. The other one was for the Nationwide System (E/F), and secure voice. All of WHCA and USSS FM locations in the Washington DC area terminated there, as well as the Echo/Fox Nationwide air-to-ground Communications for AF1. The old E/F console built by Mario Lilla was operated from WHCA's M St location until Crown Radio was moved to the OEOB shortly after the new WECO 608 was cut into service there. Crown Radio (CR) went operational for the first time in the mid-sixties. At the time CR was that it only controlled the E/F network CR was manned and operational only in support of a POTUS mission. The only radio phone patches from CR was to WH Signal board who handled connections to telephone subscribers, and CR only operated the air-to-ground E/F network.

|

| Crown Radio the E/F radio Console |

The system is operated by the White House Communications Agency (WHCA), and AT&T. Ground sites (there are about 30 of them) for the E/F system are located on AT&T microwave towers throughout the US and are connected by leased lines to a tech control console ("Crown Radio") that is part of the White House Switchboard ("Crown" or "Signal"). Each individual site can be separately keyed from the console and patched into a call, thus the system is capable of handling several calls at once although the aircraft involved have to be far enough apart not to interfere with one another.

The E/F system is completely manual at both ends, call setup and ground site selection is done by operators. On the ground the operators are WHCA/White House switchboard operators, on the aircraft they are CSO (Communication System Officers) who are military NCO's (tech sergeants mostly).

The E/F system is in-the-clear UHF full duplex voice. The aircraft often push-to-talk keys its transmitter, so it only transmits when the party on board is talking. The ground site usually transmits continuously for the duration of the call.

The system has been recently used with STU-III's for security, but apparently not too successfully. There have been occasional attempts in the past to use other kinds of secure voice, but most calls are still in the clear. Recent White House staff people who use the system have been made aware that listening to it is quite popular among scanner hobbyists and have been fairly careful about what they say, but when the system was first installed in the late 60's and early 70's there were some interesting conversations on it.

E/F antennas on AT&T towers are small and not very conspicuous but they can be recognized if one knows what they look like. They are always mounted at the top of the tower near the Hogg horns. There are usually three antennas, two small ground planes and a short vertical pole mounted above them and three or four feet apart.

Air Force One mostly uses the E/F system for actual phone connections when it is out of range of other systems or there is extremely heavy traffic on them (but it always maintains contact via E/F when in range of a ground site as backup anyway) and has in the past sometimes used E/F as a communications order wire to set up calls on the other systems.

|

| Echo-Fox antenna cluster atop an AT&T tower |

Note: Echo-Fox is no longer in service; it is reported to have been shut down in 1996.

Coverage Map

This green-shaded area on this map shows the estimated coverage of the Echo-Fox stations listed in the table above (indicated by black dots), assuming a 200-mile range for each transmitter:

| |

|

Echo-Fox Radio Sites as of March 1973

AT&T Corporate Security has requested that the names and exact locations of certain active facilities not be published; therefore, such installations are identified only by their Common Language Location identifier (CLLI) codes, printed in all capitals.

|

|

|

|

| Long Lines |

| |

|

| Mountain Bell |

|

|

| Long Lines |

|

|

| Long Lines |

|

|

| Pacific Tel. & Tel. |

|

|

| Pacific Tel. & Tel. |

|

| Pacific Tel. & Tel. |

| |

|

| Long Lines |

|

|

| Southern Bell Tel. & Tel. |

|

|

| Southern Bell Tel. & Tel. |

|

|

| Long Lines |

|

|

| Long Lines |

|

| Long Lines |

| |

|

| Long Lines |

|

|

| Southwestern Bell |

|

|

| Long Lines |

|

|

| South Central Bell |

|

|

| New England Tel. & Tel. |

|

|

| Long Lines |

|

|

| Long Lines |

|

| Long Lines |

| |

|

| Long Lines |

|

|

| Mountain Bell |

|

|

| Long Lines |

|

|

| Bell Telephone of Nevada |

|

|

| Long Lines |

|

|

| Long Lines |

|

|

| Long Lines |

|

|

| Long Lines |

|

|

| Pacific Northwest Bell |

|

|

| Southern Bell Tel. & Tel. |

|

|

| Northwestern Bell |

|

|

| Long Lines |

|

|

| Long Lines |

|

|

| Southwestern bell |

|

|

| Long Lines |

|

|

| Long Lines |

|

| Long Lines |

| |

|

| Pacific Northwest Bell |

|

|

| Pacific Northwest Bell |

|

|

| Mountain Bell |

|

Adapted from Bell System Practice 406-116-100, Issue 2, March 1973, pp. 6-7, table A

Interview of Maj. Gen. Jack A Albright The White House Communications Agency (WHCA) | |||

| |||

Type Of Activity | Communications support for the White House | ||

Location | |||

Location | Washington DC, worldwide | ||

Date of Activity | 1965 to 1989 | ||

Coordinates | |||

DATE: December 11 , 1980

G: Well, how did you get your people out?

A: It started ringing and rang till you picked it up. Not continuous, it was a buzz really, b-z-z-z, like that, and it continued to buzz two seconds, three seconds. Then it would stop and again in another two or three seconds and so on.

Well, Bobby had a briefcase in his lap and never opened the briefcase. What we found after they left is, he had a high frequency buzzer in there that buzzed all the time he was in there, ultrasound, where it was just getting enough of the sound on to that microphone, you couldn't hear anything except the noise. R-r-r-r-r-r-r-.

A: Negative, nothing. No, he was very, very careful. I know that office very well, there's nothing in there. But the tape recorder was there if he chose to use it only for telephone calls. There was no microphone in there. He couldn't record anything.

So, he gives me the invoice. Now the sets are not even here. All he did was give me the fifty invoice, and the price of it and so on. They called and put them on a Northwest Orient airline out of the Sony factory, delivered them to New York. I had a man waiting in New York, took them off the airplane, got another plane, brought them down, and I delivered them to the President somewhere around nine or ten the next morning.

G: You bet. You bet.

A; Oh, yes, we ran that, too, the two in his office. That was AP and UPI, those were the news releases, the Associated Press and United Press International. They were on two machines side by side. We had to put a shelter over them to keep the noise down. He'd go along and look at these things and read the paper coming out of the top. Sometimes they didn't work right. He'd call and give us hell, say, "Get over here and straighten this goddamn thing out," and this kind of stuff. So, we did.

G: Do you recall any other occasions where you woke the President in the middle of the night on something important?

G: What would you do if he wanted to drive the amphicar, for example?

So, we had a multiple tape preparation machine that would make up to six tapes. Play it off a master and you make six other tapes identical to it. And that's the way we made it. Once in a while he'd want to release maybe six tapes, ten tapes, fifteen, and so we made them through that.

|

Interview of Maj. Gen.

Jack A Albright |

|||

|

|||

|

Type of Activity |

Communications support for the White House |

||

|

Location |

|||

|

Location |

Washington DC, worldwide |

||

|

Date of Activity |

1965 to 1989 |

||

|

Coordinates |

|||

This is the second part of an interview with Gen. Jack

A. Albright the second WHCA commander who served from Apr. 1965 to June 1969

under Presidents Johnson and Nixon

DATE: December 11 , 1980

INTERVIEWEE: JACK ALBRIGHT

INTERVIEWER: MICHAEL L. GILLETTE

PLACE: Cosmos

Club, Washington, D. C. Tape 1 of

1

INTERVIEW II

G: You were going to talk about that trip to the Truman Library.

A: Yes. That was an interesting trip, because we went out the day before to visit and to plan for this. When we arrived at the Library, President Truman was there and [he was] a most gracious host. He came to us, and he said, "Well, you know, I always admired Lyndon. He was a great, great man, a great majority leader. And he is making a great president. You know, I wouldn't offer this for just anybody, but I would really let him and be glad to have him use my podium." I said, "Mr. President, may I see the podium? He is rather tall and maybe it is too short, maybe we can raise it. We would take a look at it. We'd like to look at it." So, he said, "Fine."

He took us to a back room. Now, he had led us through the Library; he had already walked us through the various rooms and [was] proud of the Library. He showed us the various rooms within there, and then finally found a room where this podium was stored. I do not think I am exaggerating, it could not have been more than four foot, four inches, four foot five. It was extremely short, hit you about your navel. Not something I could have used at all, and about that wide. It might have suited him very well, it might have made him loom large to the crowd in front of it, or behind it to speak. But I did not think the President would be happy with it at all, and so I said, "Mr. President, I do appreciate it, but I don't believe that it would just fit the circumstance, I don't think." He said, "Well, couldn't you put it up on some telephone books or something of this nature and sort of raise it where Lyndon could use it? He's taller than I am." I said, "Yes, sir, but we've found that they've gone through trying times on security and they really feel they need the protection now. What we have done, Mr. President, we have placed certain security within that podium, and so we would prefer to use the regular podium, which is wide, which is about his height. So, if you do not mind, we'll use that one." "Well, that's fine," he said, "whatever you want to do. But I wanted to make the offer and let you know how I felt about Lyndon. He's a great guy." So, we put his podium in and the President spoke from his regular podium, not that of President Truman.

But it is just interesting the attitude, the solicitude he had toward this. But he took all of my other people, the people that came in with me, the public address systems, and he was most solicitous, most anxious to assist, to do anything he can to make sure this was a success. We were, that morning, about, oh, three hours away from presidential arrival, and he was saying, "We've got to have it right, we've got to have it right." We knew that, of course.

G: Did you have an opportunity to see the two men together, to observe their interaction?

A: Oh, yes, many times. Each year I would say, and you will see it down through the schedule, President Johnson, sort of around the birthday period, he would visit President Truman.

I think

probably the last time I recall was in it was 1968, could be 1967, but in that

time frame, and he visited him. We went to the house, and they stood together

on the porch and took pictures and so on. Afterwards President Truman

said, "Well, I’d like to go back to

the airport with you," and Bess Truman just said, "No. Harry, it is time for your nap.

I'm sorry, you're not going to the airport." He turned to Lyndon and said, "You see, as you get older you have someone boss you around and tell you what to do. You have to look forward to this." That sort of laughed it off and ended the subject, but he did not go.

An interesting story with that though. In an earlier visit to their home, I think it was probably in 1966, we went in. Normally before the President's visit we used to install telephones in the facility, in the location where the President would come, both for Secret Service and for the President. But Mrs. Truman told my advance man, she said, "I am sorry, we don't have a phone. Don't have a phone in the home." I thought that was rather odd. Nevertheless, she said, "It's true. We do not believe in phones. We don't have a phone in the house, and if we need to use a phone, we go down to the phone booth on the corner." I thought that was rather [odd]. But she said, "Now, Lyndon's coming. He is always a great favorite of mine.

We'll let you put a telephone on the back porch with a long cord, and if he gets a call, he can bring it in the kitchen and talk on it." And that is all we could do. He put a telephone installation on the back porch with a long cord, and he did get a call and took it into the house and talked in there.

Well, at the end of that visit, as they were coming from one of the functions and going back into the house, a lot of the photographers were following and the White House photographer, [Yoichi] Okamoto, was attempting to follow. She stopped him and said, "Hold it just a minute. I don't allow photographers in my house." He said, "Why?" She said, "Well, I've got furniture that dates from World War I, old furniture. It suits me, it suits Harry. But I do not want anybody taking pictures of it, I do not want anybody making fun of it. We are not going to have it. You, you are little old Japanese boy, you get off my porch." She told Okamoto this. Okamoto said, "Look, I'm the White House photographer. I'm working for President Johnson." She said, "I don't care who you work for, you get off my porch. I don't want you on my porch." So, he came out in the yard.

Bob Taylor and

I were standing there during the argument. We were always the kidding kind, and

we joked with him a little bit and said, "Oh, you Japanese kid, get away

from us. You're terrible." Of course, we had been friends of Okamoto for years.

But we said, "You get away from us." He was really burning about

this. But she would not allow them in the house. No photographers, and specifically

Okamoto, no way. They did take pictures on the porch, and that is all they

could do.

G: Was LBJ apprised of this situation later?

A: No, no. No,

no. We never told him about that. It

really was not a thing we would

tell him about. It was just laughable to the Secret Service that heard

it. Well, the press around it heard it. The press

was really told, "You can't come in."

They never wrote much about it,

because they had great respect for Mrs. Truman and President Truman. Never said

much about it.

G: LBJ presented Harry Truman with the number one Medicare card, didn't he?

A: Yes, but I do

not remember much about that. I was not

privy to that or present at the time he did. I do recall that he did, I read

about it. But I do not know much about that.

G: Do you ever recall him talking about President Truman after these visits?

A: Oh, he would always have some comment about it.

He would inject it in some speeches.

One speech, he made it and went on to make a speech somewhere else--I think San Francisco.

He made the comment he had seen him at the Muehlebach Hotel. This was sometime

in early 1965. He made the comment, "I've just been with one of the

greatest Democratic presidents since

Roosevelt died. Old Harry Truman, I visited with him at the Muehlebach. He's one of the greatest,

and he's doing great." [He'd] just

tell the people, he said, "He's a wonderful guy," that kind of compliment,

always that kind. Nothing but compliments about him. He had a genuine respect for him. Part of

it was palaver and politics, we knew

that. But nevertheless, there was a genuine respect for him. He did not have to make those trips. He gained

maybe politically from it, but he did

not have to make them. He could have gotten public respect otherwise.

G: Did he ever

get any advice from Truman during these visits?

A: You could not tell.

G: Really?

A: We never

were privy to any of this where they talked together. You really had doubts,

because their talks were never long enough or private enough to feel that he

could. And what we saw of President

Truman, ex-President Truman, in later years did not lead us to believe that he

would. He really did not keep up with current events that close, I do not really

think so. He might have gotten political advice; I do not know that. But I do

not think in world events, no. I do not think so. President Truman was all

interested in what he was doing, in terms of the Library, in terms of what he

was doing day-to-day. But he never

attempted to talk to me or to my people, and I have spent hours with him over a

period of time, in and out of his office there in the Library, there and the other

times. He never got onto current events or onto politics. He never branched in

that area. Always sticking to current, trivial subjects. So, I have my doubts

about it, but I never heard anything.

On this particular trip we were informed of this only the day before the trip actually occurred.

G: This is the trip to Honolulu?

A: The trip to Honolulu, which is right. They chose the Royal Hawaiian Hotel, and we were given [the third floor], and all the guests were cleared off. My memory may be faulty, but it was the third floor. We cleared it all out. That was given to the presidential party. Now, the hotel itself is an old hotel, it is probably one of the older ones in Hawaii. It really had not many of the modern conveniences; it did not have air conditioning; it did not have modern communications.

We had to literally start from scratch and wire the hotel. The main frame for it was on the roof, so we had to wire from the roof of the hotel--hang the wires over the side of the hotel and string them in the windows of the various suites on the third floor and apartments and rooms.

During the night that first night, which was a Friday night of it is the second February 1961, Jack Valenti was sleeping, and we were laying wires across his bed, stringing wires across his bed. He woke up and wondered what in the world is going on, and they explained what it was, and he went back to sleep.

But it was an interesting trip in that it showed that you could in fact [handle it].

That was the

first--not really an overseas trip, but it was the first trip he had taken outside

of the continental United States with us. It had been so long since we had made

an overseas trip that the whole organization was out of practice for it, Secret

Service as well as us. So, we had to get back in swing.

G: What lessons

did you draw from this experience? How did you streamline your operation?

A: The main thing is, we found we had to develop a

bit more flexibility, more mobility with our

equipment. As he did out there on this, he changed his mind during the trip. He wanted

to speak at the East-West Center, and we had nothing at the East-West Center.

This was all in a matter of hours we had to arrange things. But we had to learn

to get equipment that was flexible to the point--and the East-West Center was

at the University of Hawaii. We had to get equipment that would match equipment

as we would find it. Sometimes they develop a low level or low resistance

speaker system, and you could go in and connect up without any problem. Others

it was a high ohmic system and you could

not do that. You had to have equipment that was especially designed and matched to it. So, we had to start carrying both,

equipment that would match both systems, and that is what resulted from that

trip. We built our travel packages considerably different as a result of that

one trip.

The other

main thing we learned was that we are almost totally dependent on in any trip

the commercial communications systems that exist, whether it be an AT&T or

GT&E or an independent, we are totally dependent on them. Because we had to

take over whatever systems exist, and they had to do the wiring; you had to depend

on that group to do the wiring locally and change all the telephones out, change

them back to our switchboard. Now, we did it within the twenty-four-hour time

frame we had, but it was not a simple thing. But without them it would have been

impossible. No way. We could not have done it ourselves. As many people as I

had, I could not have made the adjustment.

Witness that

a year later when I will talk later about the second trip to Hawaii, when we

went out in preparation for the visit out there in 1967 [1968], just before Martin

Luther King was killed. We had to abort and go back a week later. Now that is a

massive trip we prepared for that time and yet we were better prepared because

of this first trip, because we knew what we had to do, what we had the plan for,

and what we could do. So, it was a good traveling experience. But he really had

not traveled anywhere in what we called an overseas environment up to that

point, not anywhere. That was the first one.

G: Why do you think he did not travel more outside the [states]?

A: Oh, his

politics were mostly domestically oriented. He felt when he took over as president

after Kennedy was killed that he had a mission to try to pass the legislation that had been unable to pass,

that Kennedy espoused but could not pass. So,

in the first hundred to hundred and eighty days he had an objective to

pressing for that legislation. He had a control, a way with the Congress, that

no president before him has ever had.

G: Now at that East-West Trade Center he, as I recall, gave very enthusiastic support to the idea of educational television.

A: That is correct, he did. That is the first time he had ever spoken of that in public, and he spoke of it very strongly and it gave a boost to all of the ETV programs throughout the United States. But that is where it opened, that is where it began.

G: Can you recall the genesis of this? Did he ever discuss this with you?

A: No. No. That was not anything I even knew about; I

did not see it. He did not prepare for those

kinds of speeches when he was going on the road. He would have some speech

writer, Doug Cater or somebody, write him a speech. Then he would give it--he would

not rehearse it. The only speeches I

ever got involved in in preparation for

was like State of the Union or one where he is going on nationwide

TV or where he was going

to make a press conference.

Sometimes he would rehearse those kinds of things, and I got in on it, but not this kind.

He considered

those more extemporaneous types of talks. (Interruption) We were traveling from

Stewart Air Force Base in New York over to Ellenville, New York. The motorcade was traveling around through the

countryside. A crowd would gather. They had heard something about it on the

radio, and they would gather along the roadside

as we traveled through. He would stop the motorcade and get out and talk to

them. Sometimes it would be five, seven, sometimes ten or twelve people. He

would talk to all of them, wherever he

could. But as we were traveling and close to Ellenville suddenly

the motorcade stopped. And we did not know why. I did not know why. I

was in about the seventh or eighth

car back in the motorcade. When it stopped to a dead standstill, I went forward to see what it was, and here is a horse lying in the road. It

looked like a fairly scrawny-looking horse, maybe of a

trotting horse vintage, that kind, because that

is trotting horse country up there. And the farmer is standing there

talking to the Secret Service and the first lead car, which is a police car from

the state of New York, and he is irate.

He said, "You killed my best racing horse and I want to get paid for it." Well, he was not going to move the horse, nor let them move the horse until he got paid for his horse.

So, we had argued for oh, anywhere from five to seven minutes and suddenly the President gets out. He is about the third or fourth car back. He gets out and comes up and says, "What's the problem?" So, they told him.

He said, "Well, no, now he doesn't. He is dead. But he was worth that." He said, "What would you take for him?" He said, "Well, I'll take a thousand dollars." The President said, "I'll give you five hundred." He said, "Well, I'll split the difference, how about seven-fifty?" He was a trader, too, you know. The President said, "Okay, seven-fifty." He turned to the Secret Service [man] and said, "Pay him." The Secret Service [man] said, "Pay him? We don't have any money." He said, "Who's got money?" And he said, "Albright. He's the only man who carries money with him." I always carried an impress fund in cash. The President turned around and said, "What's the problem? Pay the man and let us get on! We're going to Ellenville!" So, I drug out seven hundred and fifty dollars paid the guy and got a receipt for the thing, one dead horse, got in the car and we went out.

We get back to Washington, and I do not know, we went on to these other locations here. It was to Vermont and Lewiston, Maine and New Hampshire and New Brunswick and finally to Campobello Island and back home.

So, the following week, it was the twenty-first, twenty-third [August 1966], somewhere in there, I submitted my voucher to clear my account. I put on there "One dead horse, seven hundred and fifty dollars." It got to the finance officer, and he called me, "You've got to be kidding! You can't put a dead horse on your finance voucher." I said, "Oh, yes I can. That is what happened. You see the receipt for it?" He said, "Yes, but that's not a deductible item." I said, "Oh, my God, I got a novice here."

G: He met with

Lester Pearson in Canada; I think?

A: In Campobello,

that is right he did.

A: No, other than the fact that they had a meeting, and they made no real speeches, they made no communiques from it. But they had this speech up there and they met up in FDR's old house up in Campobello Island, what they call FDR's hideaway or something--Shangri La I guess is what they called the place up there.

G: Did he ever talk about FDR when he was there?

A: Not a great deal.

Oh, he made a few comments about it, "one of the great presidents" and so

on. He really

was not one to dwell on history that much. In private

he never had much to say about it. (Interruption)

This

particular trip was the first place we had done the research work on the

nuclear development, and it is the first peaceful development at Pocatello

[Idaho]. He dedicated a space science building there and accepted an honorary

degree from the University of Denver thereafter, he went on down to Denver to

accept it. But the first site--we had been

out and prepared a site for them. We anticipated about ten thousand people to

come and hear him. So, we contracted with a local firm to put in a public address

system for him. We had some huge speakers,

amplifiers, but he was also contracted to be on nationwide TV, and so we had

connected for that. Just as all the preliminaries--the Governor of the state of

Idaho and so on all were there to make their preliminary political talks and

introduce the various dignitaries.

About the time the President got up, the public address system quit. It literally quit, nothing. So, my people were scurrying out in front, pulling plugs, and shoving this and shoving that, trying to figure what was wrong.

The President was up there and looking around at me and looking at Marvin Watson out of the corner of his eye, and Marvin [was] saying, "What's wrong?" And I would say, "Keep talking, keep talking." Well, I wanted him to keep talking because it was on nationwide TV. Well, he did keep talking. He kept making snide remarks about it, you know, "the public address system don't work, they wonder what I'm saying out there. But I hope you people out in TV can hear me" and so on. He did talk for four-and-a-half minutes and finally it came back on. He finished his speech and got back on his helicopter. I got on another helicopter.

We flew back over to the air base and flew down to Denver, which wasn't a long flight, he called me in and said, "What happened?" I said, "Mr. President, I really don't know. I'm waiting for a report." I had a fellow on the ground--a Major Taylor, Joe Taylor, and I said, "I'm waiting on him to tell me." Now some of that is in this other thing [Interview I]; you will see some duplication. But that is where it was. I said, "Well, I don't know, but I'm waiting on a call from Joe Taylor."

Well, I finally subsequently got hold of Joe Taylor, and he told me, said, "Well, we had what is known as a hot short, a hot solder. As it got hot, the solder"--that's S-O- L-D-E-R, see, I've spelled it all wrong in the early interpretation of this thing. But it came apart. As it got hot it broke loose, and that is an unusual type of a defect in electrical equipment. But it did. The President said, "My God, I'm glad you found it." I made the mistake of saying, "No, we didn't find it." He said, "You mean it could have quit again?" I said, "Yes," and he augured right through the roof.

You are

standing there with ten thousand people looking at you and they are

watching your chops moving and somebody is saying, 'What in the hell is he talking

about?' Really, that is a critical thing; you do not want to do that. Stop me next

time!" But, well, I did not ever stop him. I never stopped him again.

A: Oh, yes. My

God! It happened a number of times. (Laughter)

That's just one of many, but it was not

as obvious to him as that one. I had failures a number of times after that.

Going back a bit, we had a pre-trip group that made the trip. We left on the first day of October,1966, and we got back on the sixteenth. We turned around and left with him on the morning of the seventeenth and went back with him again for the same trip. We were dead, dead on our feet.

But at any rate, his trip, we arrived in Hawaii on the seventeenth. He got there and spent the night. Raining like hell, we got off the plane, just pouring rain. I mean just buckets. Every cable was up off the ground and the system was muffled in part at the airport because of the water on the cables. It was not a good arrival at all.

But anyway, he went downtown, spent the night. As a matter of fact, he did not spend the night, he just stopped there and made a speech and went on to Pago Pago.

Now in Pago

Pago we stopped again for the ceremonies, and we had ceremonies there while

they were refueling the plane. He made a couple of speeches there. The most interesting

thing is they had the native dances and the native ceremony. He had to drink

some of this kava, and some of this is pretty horrible brew that they come up

with out there, highly alcoholic but tastes like a very bad bitter coffee, but it

has got some native fruits and stuff in it. He would make a face and so on. But

anyway, he drank that stuff.

Then we went on to Pago Pago--that's American Samoa--and then finally wound [up] in Wellington, New Zealand. Now this was an interesting trip. He spent I believe a full night there. Yes, that is right, one full day. We went up to visit the Maori village up in the hills and then came back and visited and he spoke at the New Zealand congress.

He made some

trips around town to a couple of historical sites there. An interesting trip

went on very well. But we had enough notice, we had people in place. It is one

of the few times for President Johnson I was able to prepare

for him. Most of the time he really sort of gave you one day or two, and then

he'd give me hell and smile at me as [if] to [say] "See, I told you could do it. No problem at all."

A: He flew then, right, to Canberra. Canberra became our center of operations, and from Canberra, we stayed there I guess two days, flew one day over to Sydney, flew back to there.

I do not know

what came out of it, but one that came, we had a picnic out at the Ambassador's ranch. He had a ranch, out

in the country. He put on a nice feed. I am embarrassed

to say [I cannot think of] the Ambassador's name. I can see the guy. A fellow who was from Texas, the Ambassador--

G: Well, he was there.

G: December of 1941.

G: So, you went on to Manila from there?

A: Manila, right. And they had the conference there in Manila. We were there --they show here as two days.

G: This was the

conference with the other heads of state.

A: Southeast Asian Conference, that is right. Now he spoke to almost all of them during that time frame. Some of them he was trying to reach some sort of a consensus with them. I do not know whether he did or not. He made a number of talks while he was there.

G: Was he pleased with the way it was going there? Did his mood seem positive?

A: Yes, I think so. He felt that he was being supported in general by that crowd there that he met there, particularly the Thai and the Malaysian group, because he agreed at that point, and we then consented to modify it to continue on. We had already done some preliminary work, but he would not if he had not met them there and made some sort of an agreement to continue with them. We went on from there to Thailand and then into Malaysia.

One of the interesting things that came out of this, and I got one of the chewing’s I had. They had a rice institute down south of Manila and he went down to make a speech at this rice institute. This was arranged by Tyler Abell. Tyler Abell was [assistant] postmaster general at that time, but he was also an advance man on this particular trip.

We went down there, and we planned for this presentation, and Tyler Abell came in at the last minute and started changing things around. But he was just about to screw things up good, when I heard about it and I overruled him and said, "No, we're not going to do it that way." He had taken the President's podium out. The President would get mad. He would come in and if he did not find the circumstance, he liked in a presentation view really, he would get very unhappy. So, he told me later, "You're not going to let somebody like Tyler Abell tell you what to do, are you?" I said, "No, I'm not," and he did not. But we put it back in place. We moved Tyler Abell out and shoved him all up to Korea. He went ahead of us on a jump to the Korean site.

But he made the speech at the rice institute. This was generally where we agreed to provide some assistance to that rice institute to try to proliferate the fast-growing rice that they had come up with, very prolific rice for Southeast Asia, for Malaysia, for Thailand and for Vietnam. They agreed to move some of that out there under the auspices of that rice institute.

G: He did go to Vietnam then, didn't he?

A: He went to

Vietnam the following morning. I was rudely awakened at two o'clock. I knew something

was wrong. I knew that something was going to happen, because I was told

to be at the naval base at Subic Bay at something like five-thirty, six in the morning.

Well, I was. I was the only member of my group that could be there.

Nobody else from the White House Communications [Agency] was there. We got on a plane, the President's plane, the single 707, the presidential aircraft, and flew to Vietnam.

Then we got there. So, he told me, he said, "I'm going to visit the troops in the hospital. When I come back, I want to have it set up for a speech." I said, "Well, I'll be able to record it. There's not going to be any podium." He said, "Where is the podium?" I said, "Podium? You would not let me bring anybody. You just told me, and I am here all alone. I have got microphones prepared for your speech and we will record you, but you are not going to talk into any podium or anything, presidential podium. There is not going to be any presidential seal. You're just going to get up and talk to the troops, Mr. President." Well, he said okay. He sort of accepted it, but some of the other aides there thought I should have brought the whole--and I said, "Well, that's really wonderful to think. That is a four-hundred-pound podium, and you have got me here alone. So." He did talk to the troops. We fixed it up, and we recorded it. It was a very, very hush-hush trip, a lot of security involved in the thing. He really had told [General William] Westmoreland that he was coming, and that is about the only one that knew there that he was coming into there.

G: How did he feel about that trip? Did the experience influence him in one way or another?

A: Well, yes, it did, it sort of touched him. Because on the way back he would talk to us about it; he talked to me about it and a couple of others, Marvin Watson, Jake Jacobsen, a couple of others were on there. He felt he had really had a meaningful trip to him. He felt he had done something that was important to the troops in Vietnam. He always felt strongly about Vietnam. He felt that it was right, he felt we were doing the right thing. Even though, as he says, his detractors did not feel that way, he felt that he was.

G: Did he also feel that it was important for him to be there to show a measure of support for the troops?

A: Yes, that is why he went. He would not have

gone otherwise. He really felt that it was important. He did not feel as many

people did that, he was putting his life in danger; he never felt that way. He

never worried about his life really, per se. He never felt there was anybody

that was really anxious to kill him.

G: He never had a fear of assassination?

A: Not at that time, he did not. He developed some of

it later, but not at that time. And certainly, out there he had

no fear. These were among his people. These people in Vietnam were his--you

ask the British, the Australians, whatever was there for him were all friends of his. They were people that were supporting the same things that he supported, support for

the Vietnamese. And certainly, the Vietnamese that he dealt with, they were there, they were still in power because U.S. forces were there. And

so, no, he had no concern about that kind of visit; he felt good about the visit.

But an

interesting thing happened. Interesting thing looking back on it, it was not too

funny at the time. As we left there, he asked me, "Did you get a copy of

the tape?" I said, "Yes, we brought one and I have one." He

said, "Well, I tell you what, I want to go on nationwide TV when I arrive back

in Manila." International TV. And I said, "Mr. President, fine, all

right. We can probably arrange this. It probably will be tape recorded, and we would

have to go out to one of the TV studios and record. I can arrange that."

He said, "But I want to use the teleprompter." I said, "Now wait

a minute, Mr. President. I asked you specifically, you personally, did you want

us to bring the teleprompters before we came and you said, 'No. it's too much weight.' So, we did not bring

it. That is some we cut out, six hundred pounds. We just cut down in the weight

of the things we were hauling around. And you said, 'All right, don't bring

it. It is too much!'" I said, "You don't have them." He said,

"Well, don't they have those out here?" I said, "No! They do not

have them all over the world! They might have some elementary ones in

Japan." He said, "Well, I

don't care where you get them. Get me

one by tomorrow morning!" I said, "Well, I'll try, but I'm not betting that I'll have it." He said, "Well, I don't tell you all my

problems. Just find one."

Well, I called back to my people in Manila from the air after we took off from Cam Ranh Bay and I told them what I wanted. Then I had an incredibly good man in Manila, Jack Rubley, who is now the head of communications for the ICA, Interagency [International] Communications Agency. I said, "Jack, the President wants to make a TV recording and go on worldwide TV. So, you are going to have to record it in the morning; when he comes back, he wants to record. It is going to be late at night. But he wants to go on the TV." He said, "Well, would he be willing to wait until in the morning? I can get him on nationwide TV easier in the morning. Time-wise it's just not right tonight." "But," I said, "he wants the teleprompter." He said, "You know we don't have a teleprompter out here." I said, "I know that, and you know that. But just find one, Jack." "My God," he said, "you give me some of the damnedest jobs." I said, "Don't tell me your problems, Jack. That's what he told me." So, we left it laughing like that.

Well, when he [Johnson] got back it so happened he

changed his mind before he got home. He

did not want to make a recording

that night. He said, "I tell you what,

I'll do it first thing in

the morning. But you have it ready

at say nine in the morning."

So, okay. That would give us an overnight. But

Jack had it ready. We could have gone to

a studio and recorded it for TV that night.

But we put it off until the following morning, sent him out there and

did record it.

They had a form of teleprompter, some things that he could look at and the tape could be put on there. We

did do that, and he recorded it the following morning. Generally,

it was a short message about his feelings about his trip into Vietnam and why he went there.

G: Why did he change his mind, do you think, so

many times on things like this?

A: Do you mean on the way home?

G: No, just in general on last minute changes, last minute decisions, changing his mind on whether or not he wants to use this or wants to speak from this podium or that podium, and things like that.

A: I never did figure him out really. I

never really understood him that complete. I could have understood more if the circumstances had changed or

if there had been an incident or something to upset him or if somebody had

called and told him about some press release or something. But I did not often

see those things that caused them. But I concluded in general he got tired. Maybe

the circumstance appeared to change for him, and so he would say, "Well, okay, I'm tired tonight. We are not going

to do it tonight. Let us change it

and do it in the morning." I have to adjust

it maybe to tiredness, maybe to his age, maybe to the fact that the trip itself

was bearing on him. I never was critical of him

for doing this. I just reacted to, that was all I could do. And there were

times [when] I was there, yes. I moaned and groaned about him doing it.

But in retrospect, no, I think

that some of that was just a fact of the pressures of the office.

(Interruption)

Before we left, we were preparing to leave the Philippines and about that night, it was somewhere around two o'clock in the morning, I get a call from Korea. My advance man in Korea tells me, said, "We got a problem up here." "Now," he said, "the problem is, we wanted to use a podium, the President's podium, up here in Korea but we got a fellow by the name of Tyler Abell who sent some advance word up here. Hackler is here, Loud Hackler"--he was acting as the advance man on that particular trip--"but the y say no, we've got to use one that's built in, that's short, that fits the Korean president and matches the decor and all this stuff, and they've gone ahead and had it built." And it is high. Oh, it was a massive speech environment. He was trying to speak to about two million people from a conjunction of a whole series of where roads radiated into a square, I do not know, it was seven, eight, ten roads came to one point in the center of Seoul. A massive and a very impressive sight. But we had built this thing up off the ground, some seventy-five or a hundred feet, and looking down these roads you could see this thing from all directions. So, they were going to make sort of a dais, a real impressive affair. And they did not think this President's podium would fit in that environment or would show.

I said, "Look"--this is my man, it's Jim Adams, and I said, "Jim, look, please. The President told me again tonight, he said he wants to speak at that podium up there. So, do not argue with him and we are not going to take any argument. Tell them to put that podium up." So, he said, "All right. I'll tell them."

Well,

another hour later I am now asleep. I am in the hotel in Manila asleep. I get a

telephone call and he said, "Sorry. They say nope, they will not do it. They're

not going to do it." And I said, "Who do they want to call them?"

He said, "Well, they want Marvin Watson to

call them if there's a change. I said, "Marvin isn’t going to like it, I'm going to wake him up." So, I called him and woke him up.

"Yes, Colonel, what's the problem?" I said, "Lloyd won't change

it.

Lloyd Hackler

says we're going to use that built-in podium, he will not use a presidential

podium." "Didn't you tell him

what we told you?" I said, "Yes."

"And he still insists?" I said, "That's right. He wants to talk

to you." "He'll be sorry he did. Would you get him on the phone and

then give me the call?" I said, "Yes." I said, "Okay, Jim, get him on the phone and then give it

to me, and I've got Brother Watson standing